We live in a world of silos. Silos data. Silos of culture. Linked Open Data aims to tear down these silos and create unity among the collections, their data and their meaning. The World Museum awaits us.

It comes as no surprise that I begin this post with such Romantic allusions. Our discussions of vocabularies – as technical behemoths and cultural artefacts – were lively and florid at a recent gathering of researchers library and museum professionals at LODLAM-NZ. Metaphors of time and tide – depicted beautifully in this companion post by Ingrid Mason, highlight issues of their expressive power of their meaning over time and across cultures. I present a very broad technical perspective on the matter beginning with a metaphor for what I believe represents the current state of digital cultural heritage : a world of silos.

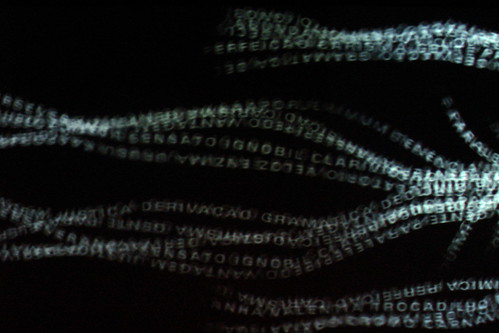

Among these silos lie vocabularies that describe their collections and induce meaning to their objects. Originally employed to assist cataloguers and disambiguate terms, vocabularies have grown to encompass rich semantic information, often pertaining to the needs of that institution, their collection or their creator communities. Vocabularies themselves are cultural artefacts representing a snapshot of sense making. Like the objects that they describe, vocabularies can depict a range of substance from Cold War paranoia to escapist and consumerist Disneyfication. Inherent within them are the world views, biases, and focal points of their creators. An object’s source vocabulary should always be recorded as a significant part of it’s provenance. Welcome to the recursive hell of meta-meta-data.

Within the context of the museum, vocabularies form the backbone from which collection descriptions are tagged, catalogued or categorised. But there are many vocabularies, and the World Museum needs a universal language. LODLAM-NZ embraced the enthusiasm of a universal language but also understood the immense technical challenges that follow vocabulary alignment and, in many cases, natural language processing in general. However, if done successfully, alignment does a few great things: it normalises the labels that we assign to objects so that a unity of inferencing, reasoning and understanding can occur across vast swathes of collections; it can provide semantic context to those labels for even deeper, more compelling relations among the objects and it can be used to disambiguate otherwise flat or non-semantic meta-data, such as small free-text fields and social tags.

Vocabulary alignment is the process of putting two vocabularies side-by-side, finding the best matches, and joining the dots.

In many cases, alignment is straight forward – a simple string match on the the aligned terms could be sufficient to create a match. However, as the above example shows, aligning can require a lot more intuition – ceremonial exchange from the Australian Museum’s thesaurus could map to the ceremonies, exchange and gift concepts from the Getty’s Art and Architecture Thesaurus. This necessary one-to-many relation, along with other possible quirks and anomalies such as missing terms, semantic differences between term use and interpretation, and the general English language bias of many natural language processing tools make such a task fraught with difficulty, especially when alignment occurs across vocabularies that address specific cultural groups.

The challenges of alignment are compounded when the source terms come from non-semantic sources, such as unstructured free text (labels, descriptions and comments) and user tags. Let’s say for example that someone has tagged an object with the term gold. Now, could they mean “this object is made of gold” or “this object has a golden colour”? The Getty’s Art and Architecture thesaurus has the term gold in both senses of the word. We could use a tool called SenseRelate::Allwords that gives us the correct WordNet concept (based on the context of an object’s description label) but then we need to align the WordNet gold to the AAT’s gold. Performing these two computations in a pipeline significantly increases the risk that the tag as ‘misinterpreted’ – or even worse, it’s original meaning and intention is skewed or lost altogether. Vocabulary alignment, if not done correctly, has the potential to dilute, skew, or destroy the meaning of its terms.

Over the past few years, elaborate algorithms have been developed to try and address these alignment challenges. However they often don’t work on the unpredictable and highly heterogenous nature of cultural data-sets, or their performance differs across and even within vocabularies. And when things do go wrong, problems are often hard to diagnose and even more difficult to solve.

But researchers have brought humans back into the equation. The idea is that, within the alignment process, machines do the heavy lifting and processing on very simple and straight-forward natural language processing tasks while humans fine tune the steps of the process until they are satisfied with their results. This paper, by Ossenbruggen et al., describes what they call interactive alignment. Their Amalgame tool allows humans to make judgements about the nature of the vocabularies being aligned, fine-tune parameters and analyse, select or discard matching results. This mixed initiative approach empowers both computers and humans to solve tough problems. Likewise, the vocabularies (or ontologies within the computer science science realm), while encoded in bits and bytes, are only realised in the minds of their creators, their users and conversely, the people that interact with the objects.

The concept of meaning, understanding and encoding – and the crucial differences between the three concepts, seeded a reflective discussion at LODLAM-NZ. Even in light of the technical issues, how can we ensure accurate alignment that preserves the sense making of the objects from both their custodians and creator communities? What vocabularies do we use, what vocabularies should we align to and why? What are the dangers of doing this? We could not find the answers to these questions – to steal an anecdote from Michael Lascarides, the best we could do is create better questions, and more importantly, a broader understanding of alignment on both technical and social dimensions.